code Text=12;

Text(0, "Hello World!")

"Text" is a built-in routine that outputs a string of characters. The

zero (0) tells where to send the string. In this case it's sent to the

display screen, but it could just as easily be sent to a printer, a

file, or out a serial port by using a different number.

begin

MakeNumber;

repeat InputGuess;

TestGuess

until Guess = Number

end

Note that the program is almost word for word the same as the description

of the task. First we "make a number" then we repeatedly "input a guess"

and "test the guess" until it's the number. There needs to be more to this program since it does not tell how to make a number, input a guess, or test the guess. Each of these operations is a subroutine to the main program. In XPL0 these subroutines are called "procedures." Here's how to write each of these procedures.

procedure MakeNumber;

begin

Number:= Ran(100) + 1

end

This procedure generates a random number between 1 and 100 (inclusive)

and puts that number into the variable called "Number".

procedure InputGuess;

begin

Text(0, "Input guess: ");

Guess:= IntIn(0)

end

This procedure displays the message: "Input guess: " on the monitor

(output device 0) and gets a number (Integer In) from the keyboard (input

device 0). In XPL0 nine different input and output devices can be called

from the program. This enables direct access to the monitor, keyboard,

printer, disk files, and other I/O devices.

procedure TestGuess;

begin

if Guess = Number then Text(0, "Correct!")

else

if Guess > Number then Text(0, "Too high")

else Text(0, "Too low");

CrLf(0)

end

This procedure is more complicated but still easy to understand. If the

computer's number is equal to the guess then we execute one statement; if

it's not equal then we execute another statement. If the numbers are

equal, we tell the user that the guess is correct; if they are not equal,

we test if the guess is high or low and tell the user. CrLf(0) starts a

new line on the monitor (Carriage Return and Line Feed). Here's the complete program:

code Ran=1, CrLf=9, IntIn=10, Text=12;

integer Guess, Number;

procedure MakeNumber;

begin

Number:= Ran(100) + 1

end;

procedure InputGuess;

begin

Text(0, "Input guess: ");

Guess:= IntIn(0)

end;

procedure TestGuess;

begin

if Guess = Number then Text(0, "Correct!")

else

if Guess > Number then Text(0, "Too high")

else Text(0, "Too low");

CrLf(0)

end;

begin

MakeNumber;

repeat InputGuess;

TestGuess

until Guess = Number

end

Two new items are shown. The command word 'code' is used to give names to

intrinsics. Intrinsics are built-in subroutines that do common

operations. For example, "Ran" is the name of the random-number

intrinsic, and "Ran" is used to call this random-number generator as a

subroutine. The second item is the command word 'integer'. This declares

a name and allocates memory space for each variable that follows it. Note that the main procedure is the last block in the program. An XPL0 program is read starting at the bottom to get the main flow and working upward to get the details in the procedures.

Here's an example of what this program does when it runs:

Input guess: 50

Too high

Input guess: 25

Too high

Input guess: 9

Too low

Input guess: 18

Correct!

It's generally a good practice to break a program up into subroutines,

but something this simple would probably be written more like this:

include c:\cxpl\codesi;

integer Guess, Number;

begin

Number:= Ran(100)+1;

repeat Text(0, "Input guess: ");

Guess:= IntIn(0);

Text(0, if Guess = Number then "Correct!"

else if Guess > Number then "Too high"

else "Too low");

CrLf(0);

until Guess = Number;

end;

The 'include' command inserts a file called codesi.xpl, which resides in

the cxpl directory on the c: drive. This file simply contains 'code'

declarations for all the intrinsics. (The ".xpl" extension is assumed

unless another extension is specified.)

\Weed.xpl 15-Jan-2009

\Plots the "Weed" function

include c:\cxpl\codesi; \intrinsic routine declarations

define S = 100., \size of plotted image (scale factor)

N = 32000., \number of points plotted

Pi2 = 3.14159265*2.;

integer X, Y; \graphic coordinates (pixels)

real A, D; \angle and distance (polar coordinates)

begin

SetVid($12); \set 640x480 graphics with 16 colors

A:= 0.; \for A:= 0 to Pi2 do...

repeat

D:= (1.+Sin(A)) * (1.+.9*Cos(8.*A)) * (1.+.1*Cos(24.*A)) * (.9+.05*Cos(200.*A));

X:= Fix(D*Cos(A)*S); \convert polar to rectangular coordinates

Y:= Fix(D*Sin(A)*S);

Point(X+320, 400-Y, 2\green\);

A:= A + Pi2/N;

until A >= Pi2;

X:= ChIn(1); \wait for a keystroke

SetVid($03); \restore normal text mode

end;

Ignore the hairy math for a moment and notice the intrinsic routine

called SetVid. This sets the video mode to hex 12 (decimal 18), which is

a graphic display mode.

Ignore the hairy math for a moment and notice the intrinsic routine

called SetVid. This sets the video mode to hex 12 (decimal 18), which is

a graphic display mode. The intrinsics Sin and Cos convert angles to their sine and cosine values. Real numbers (also called floating-point numbers) are used along with integers. The intrinsic Fix converts a real number to its closest integer.

The Point intrinsic plots the resulting coordinates on the screen.

SetVid is also used to restore the display to its normal text mode after ChIn (Character In) gets a character from the keyboard.

\Clock.xpl 15-Jan-2009

\Display the current time of day

inc c:\cxpl\codesi; \include intrinsic code declarations

proc NumOut(N); \Output a 2-digit number, including leading zero

int N;

begin

if N <= 9 then ChOut(0, ^0);

IntOut(0, N);

end; \NumOut

proc ShowTime; \Display current time (e.g: 12:03:45)

int Reg;

begin

Reg:= GetReg; \get address of array with copy of CPU registers

Reg(0):= $2C00; \call DOS function 2C (hex)

SoftInt($21); \DOS calls are interrupt 21 (hex)

NumOut(Reg(2) >> 8); \the high byte of register CX contains the hours

ChOut(0, ^:);

NumOut(Reg(2) & $00FF); \the low byte of CX contains the minutes

ChOut(0, ^:);

NumOut(Reg(3) >> 8); \the high byte of DX contains the seconds

end; \ShowTime

begin \Main

repeat ChOut(0, $0D); \carriage return moves to the start of the line

ShowTime; \call routine to show the current time

until ChkKey; \keep repeating until a key is struck

end; \Main

The intrinsics GetReg and SoftInt are used to access DOS and BIOS

routines. GetReg returns the address of an array where a copy of the

processor's hardware registers are stored. Values (such as $2C00 in the

example) can be stored into this array. When SoftInt is called, the

values in the array are loaded into the processor's registers and the

specified interrupt ($21 in the example) is called. ChOut outputs a character (such as ":") to the display, and IntOut outputs an integer value to the display. ChkKey checks the keyboard for a keystroke.

The AND operator "&" and the SHIFT operator ">>" manipulate the individual bits in an integer.

All command words, such as 'integer' and 'include', can be abbreviated to their first three letters.

include c:\cxpl\codesi; \standard library 'code' definitions

repeat Cursor(Ran(80), Ran(25)); \randomly select location on screen

Attrib(if Ran(2) then 10 else 2); \randomly select light or dark green

ChOut(6, Ran(2)+^0); \randomly output an ASCII 0 or 1

until ChkKey; \run until a key is struck

The intrinsic Cursor sets the column and row on the screen where

characters will appear. The upper-left corner is 0,0.

The intrinsic Cursor sets the column and row on the screen where

characters will appear. The upper-left corner is 0,0.The Attrib intrinsic specifies the attributes (usually the foreground and background colors) used for displaying characters on device 6. The argument "if Ran(2) then 10 else 2" is an example of an "if expression," which is different than the more common "if statement." It's equivalent to the C expression "rand()%2 ? 10 : 2". If Ran(2) returns a zero value, it's interpreted as being false; while any non-zero value (such as 1) is treated as being true. Thus the argument evaluates to either 2 (for false) or 10 (for true). These are the values of the two shades of green for EGA (and newer) video modes.

\Sand.xpl 25-Jan-2010

\Falling Sand Simulation

include c:\cxpl\codesi; \standard library 'code' definitions

define Grains = 2000; \number of grains of sand

int Gx(Grains), Gy(Grains), \screen pixel coordinates of each grain

I, Dir; \index, direction

define Black=0, Brown=6, White=7, Yellow=$E;

[SetVid($13); \set 320x200 graphics

Move(140, 70); Line(160, 90, White); \draw funnel (with thick

Move(140, 71); Line(160, 91, White); \ sides that won't leak)

Move(182, 70); Line(162, 90, White);

Move(182, 71); Line(162, 91, White);

Move(100, 199); Line(219, 199, White); \draw floor

for I:= 0 to Grains-1 do \make sand at two spouts

if I&1 \odd?

then [Gx(I):= 150; Gy(I):= 1]

else [Gx(I):= 163; Gy(I):= 20];

repeat

for I:= 0 to Grains-1 do \for all the grains of sand ...

[Point(Gx(I), Gy(I), Black); \erase grain's initial position

if ReadPix(Gx(I), Gy(I)+1) = Black \is grain above empty location?

then Gy(I):= Gy(I)+1 \yes: move straight down

else [Dir:= Ran(3)-1; \no: randomly fall right or left

if ReadPix(Gx(I)+Dir, Gy(I)+1) = Black

then [Gx(I):= Gx(I)+Dir; Gy(I):= Gy(I)+1];

]; \draw grain at its new position

Point(Gx(I), Gy(I), if I&1 then Brown else Yellow);

];

repeat until port($3DA) & $08; \wait for vertical retrace

until ChkKey; \continue until a key is struck

SetVid($03); \restore text mode (for DOS)

]; \that's all folks ...

First, note that brackets [ ] can be used in place of 'begin' and 'end'.

This should make C programmers feel more at home.

First, note that brackets [ ] can be used in place of 'begin' and 'end'.

This should make C programmers feel more at home.A couple new intrinsics, Move and Line, are used to draw a funnel and a floor. ReadPix returns the color of a pixel, and thus is the opposite of the Point intrinsic.

Besides the 'repeat' command, a common way to repeatedly execute some code is with the 'for' command. Here it's used to execute blocks of code that manipulate each individual grain of sand.

The last new item is the 'port' command. This provides access to the PC's input and output ports. Here it's used to detect the video system's vertical retrace signal. Since this normally occurs 60 times per second, it's used to regulate the speed of the animation.

\Puzzle.xpl 8-Feb-2010

\Sliding Block Puzzle - match the numbers with the keypad

code Rem=2, ChIn=7, ChOut=8, CrLf=9, Clear=40;

int Box, Key, Hole, Tbl, K, I;

[Box:= [0, ^1, ^2, ^3, \starting configuration

^4, ^5, ^6,

^8, ^7, ^ ];

Hole:= 9; \index for hole position

loop [Clear; \show the puzzle

for I:= 1 to 9 do

[ChOut(0, Box(I)); ChOut(0, ^ );

if Rem(I/3) = 0 then CrLf(0);

];

Key:= ChIn(1); \get move

K:= Key - ^0;

if K>=1 and K<=9 then \is it legal?

[Tbl:= [0,7,8,9,4,5,6,1,2,3]; \convert key to match Box

K:= Tbl(K);

if K-3=Hole or K+3=Hole or \can move up or down?

(K-1=Hole or K+1=Hole) and (K-1)/3 = (Hole-1)/3 \same row?

then [Box(Hole):= Box(K); \move block into hole

Hole:= K; \move hole into block

Box(Hole):= ^ ;

];

]

else quit;

];

];

Not only are brackets [ ] used as an abbreviation for begin-end's, but

they're also used to set up arrays of constant values. Here they set the

initial positions of the numbered "blocks." A more general way to form a loop besides the 'repeat' and 'for' commands is to use a 'loop' command. The advantage is that the loop can be exited at any point with the 'quit' command. (This is similar to the 'break' command used by other languages.)

The Clear intrinsic erases the screen and sets the cursor position to the upper-left corner (location 0,0). The Rem intrinsic returns the remainder of I/3, which in this case is used to start three new lines with the CrLf (Carriage Return and Line Feed) intrinsic.

Partly to make Pascal programmers feel more at home, the command words 'and', 'or' and 'xor' were added to the language. These are alternatives for XPL0's traditional symbols "&", "!" and "|"; and they perform exactly the same operations. The words might make a program a little easer to read and understand.

\Crystal.xpl 15-Feb-2010

\Tumbling Octahedron

include c:\cxpl\codesi; \intrinsic code declarations

real X, Y, Z; \arrays: 3D coordinates of vertices

int I;

define Size=150.0, Sz=0.008, Sx=0.013; \drawing size and tumbling speeds

define Color=3; \line color = cyan

\Coordinates of octahedron, ordered to allow continuous line to trace all edges

[X:= [0.0, 1.0, 1.0, 0.0,-1.0,-1.0, 0.0,-1.0, 1.0, 0.0, 1.0,-1.0, 0.0, 0.0];

Y:= [1.4, 0.0, 0.0, 1.4, 0.0, 0.0,-1.4, 0.0, 0.0,-1.4, 0.0, 0.0, 1.4, 0.0];

Z:= [0.0, 1.0,-1.0, 0.0, 1.0,-1.0, 0.0, 1.0, 1.0, 0.0,-1.0,-1.0, 0.0, 0.0];

SetVid($12); \set 640x480 graphics with 16 colors

repeat Clear; \erase screen

Move(Fix(X(0)*Size) + 640/2, Fix(Y(0)*Size) + 480/2);

for I:= 1 to 13 do

Line(Fix(X(I)*Size) + 640/2, Fix(Y(I)*Size) + 480/2, Color);

Sound(0, 1, 1); \delay 1/18 second, to reduce flicker

for I:= 0 to 13 do

[X(I):= X(I) - Y(I)*Sz; \rotate vertices in X-Y plane

Y(I):= Y(I) + X(I)*Sz;

Y(I):= Y(I) - Z(I)*Sx; \rotate vertices in Y-Z plane

Z(I):= Z(I) + Y(I)*Sx;

];

until ChkKey; \run until a key is struck

SetVid(3); \restore text mode (for DOS)

];

Although an octahedron only has 6 vertices, the constant arrays

X, Y and Z define 14 coordinates in 3D space. The reason for this is

that it makes drawing the edges a little simpler because they can all be

drawn as a continuous series of line segments.

Although an octahedron only has 6 vertices, the constant arrays

X, Y and Z define 14 coordinates in 3D space. The reason for this is

that it makes drawing the edges a little simpler because they can all be

drawn as a continuous series of line segments. The Sound intrinsic is used, with the sound turned off, to provide a short delay. This not only regulates the tumbling speed but also reduces flicker. Normally flicker would be eliminated by drawing on an off-screen buffer that's quickly copied to display memory, but for simplicity, lines are drawn (and erased) directly on the visible display memory.

The code that rotates the vertices is a simplification of the normal rotation equations:

X' = X*cos(ang) - Y*sin(ang)

Y' = Y*cos(ang) + X*sin(ang)

If you let the program run long enough, you'll see what's wrong with

this simplification.

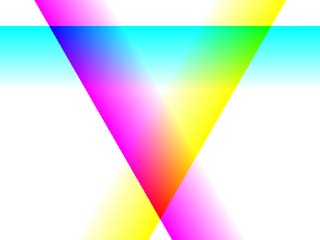

\RGB.xpl 11-Mar-2010

\Display test patterns using 24-bit color

\Compile with 32-bit XPL0 (xpx.bat - for VESA graphics)

include c:\cxpl\codes; \intrinsic 'code' declarations

int Neg; \boolean: show negative image

func DotProd(V1, V2); \Return dot product of two 2D vectors

int V1, V2; \V1 dot V2 = |V1|*|V2|*cos(ang)

int DP;

begin

DP:= (V1(0)*V2(0) + V1(1)*V2(1)) >> 7;

if DP > 255 then DP:= 0; \(also truncates negative dot product to 0)

return if Neg then 255-DP else DP;

end; \DotProd

int X, Y, R, G, B, Vr, Vg, Vb, V(2);

begin \Main

SetVid($112); \set 640x480 graphics with 24-bit color

Vr:= [ 0,-256]; \coordinates of equilateral triangle

Vg:= [-222, 128]; \ with origin at center of screen

Vb:= [ 222, 128]; \256*sin(30)=128; 256*sin(60)=222

Neg:= false; \start with positive image

loop begin

for Y:= 0 to 480-1 do \for all the pixels on the screen...

for X:= 0 to 640-1 do

begin

V(0):= X-320; V(1):= Y-240+60; \form vector from center

R:= DotProd(Vr, V); \(60 = centering fudge factor)

G:= DotProd(Vg, V);

B:= DotProd(Vb, V);

Point(X, Y, R<<16 + G<<8 + B);

end;

if ChIn(1) = $1B\Esc\ then quit;

Neg:= not Neg; \keystrokes alternate images until Esc key

end;

SetVid(3); \restore normal text mode

end; \Main

Although it really doesn't matter in this example, notice that codes.xpl

is included instead of codesi.xpl. 32-bit XPL0 has a slightly different

set of intrinsic routines than the 16-bit versions.

Although it really doesn't matter in this example, notice that codes.xpl

is included instead of codesi.xpl. 32-bit XPL0 has a slightly different

set of intrinsic routines than the 16-bit versions.In the previous examples intrinsics such as Sin, ChIn, and ChkKey were used. These each return a value and are used as values so they act as "functions" rather than as ordinary subroutines (or "procedures"). In this example a function called DotProd is defined. The command word 'func' is used instead of 'proc' to make this distinction, but the important feature is the word 'return' which is used to return a value.

Notice the difference in the way the arrays Vb and V(2) are declared. Vb doesn't need the "(2)" because the two integers are reserved in memory and set up by the constant array.

\Walker.xpl 22-Feb-2010

\Compile with 32-bit XPL0 (xpx.bat)

include c:\cxpl\codes;

proc ShowGuy(Frame, X0, Y0); \Display a frame of the walking guy

int Frame, X0, Y0; \frame (0..7), and its upper-left coordinate

int GuyImage, X, Y, Color;

[GuyImage:=

[[$00020000, $00222200, $00229000, $00099900, $000F9000, $000F9000, $000F9000, $00011000, $00F11000, $000FF000],

[$00020200, $00222000, $00229000, $00099900, $000F9000, $00F99000, $00F990F0, $000110F0, $00110F00, $00FF0000],

[$00000000, $00220200, $00222000, $00029000, $00099900, $00FF9000, $00F99000, $0FF99F00, $00111110, $0FF001FF],

[$00000000, $00222200, $00229000, $00099900, $000F9000, $000F9000, $00F99000, $00011000, $0FF11100, $0F00FF00],

[$00020000, $00222200, $00229200, $00299900, $000F9000, $0009F000, $000F9000, $00011000, $00F11000, $000FF000],

[$00020000, $00222200, $00229000, $00099900, $000F9000, $0009F000, $0009F0F0, $000110F0, $00110F00, $00FF0000],

[$00002000, $00220200, $00222000, $00029000, $00099900, $0009F000, $0009F000, $00099F00, $00111110, $0FF001FF],

[$00000000, $00022000, $00229200, $00299900, $000F9000, $000F9000, $0009F000, $00011000, $0F111100, $0F00FF00]];

for Y:= 0 to 10-1 do \for 10 horizontal scan lines...

[Color:= GuyImage(Frame, Y); \get colors for 8 horizontal pixels

for X:= 7 downto 0 do \plot pixels from right to left

[Point(X+X0, Y+Y0, Color&$0F);

Color:= Color>>4;

];

];

]; \ShowGuy

int Posn; \position of walker

[SetVid($13); \set 320x200 graphics

loop for Posn:= 0 to 320-1 do \move position across screen

[ShowGuy(Posn&7, Posn, 100); \show a frame of guy at position

Sound(0, 2, 1); \delay about 1/9 second

if KeyHit then quit; \terminate program on key stroke

];

SetVid($03); \restore text mode (for DOS)

];

Because it was convenient to pack the 8-pixel-wide images into 32 bits,

32-bit XPL0 was used. Each image is 8x10. Only the first 16 colors of the

256 colors available in mode $13 graphics are used.

Because it was convenient to pack the 8-pixel-wide images into 32 bits,

32-bit XPL0 was used. Each image is 8x10. Only the first 16 colors of the

256 colors available in mode $13 graphics are used. By masking the position with 7 (Posn&7), the 8 images (0..7) in the 2-dimensional constant array are displayed in sequence as the guy moves across the screen (0..319).

The Sound intrinsic is used to regulate speed. The arguments are: volume (0), number of system clock ticks to wait (2), and pitch (1, which we don't care about since the volume is zero).

One subtlety is that the left column in each image is set to all 0's, which is the color of the background. This automatically erases the trailing edge of the guy as he walks across the screen.

There's no penalty when the optimizing compilers are used to write 10-1 instead of 9, or 320-1 instead of 319. These 'for' loops are written this way to emphasize that they execute 10 and 320 times respectively, because they start counting at 0.

\Caser.xpl 15-Mar-2010

\Usage: caser < filename.txt > filename.doc

include c:\cxpl\codes;

int Start, Ch;

[Start:= true;

repeat Ch:= ChIn(1);

if Ch>=^A and Ch<=^Z and not Start then Ch:= Ch+$20

else case Ch of ^., ^!, ^?, ^:: Start:= true other [];

ChOut(0, Ch);

if Ch>=^A and Ch<=^Z then Start:= false;

until Ch = $1A\EOF\;

];

The "<" indicates that the file name typed on the command line is to be

used for input instead of the keyboard, and the ">" indicates that

characters that would normally go to the display screen are instead to

go to the file specified for output. In the program, ChIn(1) now gets

characters from the input file, and ChOut(0, Ch) now sends characters to

the output file. The input file must be terminated with an end-of-file

character ($1A). (Under Windows this must be run from a Command Prompt.)

The 'case' statement tests for the several ways that a sentence might end. It's equivalent to "if Ch=^. or Ch=^! or Ch=^? or Ch=^: then Start:= true".

INPUT "What is your name: ", N$ PRINT "Howdy "; N$would have to be written in XPL0 something like this:

string 0;

code ChIn=7, CrLf=9, Text=12;

int I;

char Name(128);

[Text(0, "What is your name? ");

I:= 0;

loop [Name(I):= ChIn(0); \buffered keyboard input

if Name(I) = $0D\CR\ then quit; \Carriage Return = Enter key

I:= I+1;

];

Name(I):= 0; \terminate string

Text(0, "Howdy "); Text(0, Name); CrLf(0);

];

The "string 0" command changes the convention that XPL0 uses for

terminating strings. It changes it to terminating them with a zero byte

instead of setting the most significant bit on the last character. This

feature is not available in the interpreted compiler, XPLI (x.bat). The keyboard buffer can hold a maximum of 128 characters, so to prevent the possibility of overflowing the Name array, at least this many bytes are reserved.

When the ChIn(0) intrinsic is first called, it collects characters from the keyboard until the Enter key is struck. It then returns to the XPL0 program where one character is pulled from the buffer each time ChIn(0) is called. When the Enter key (which is the same as a carriage return, $0D) is pulled, the program quits the loop. A zero byte is stored in place of the Enter key to mark the end of the string.

Since it would be too easy to write a program that finds the smallest number whose factorial has at least 100 digits (it's 70), we'll write a program that finds the smallest number whose factorial has at least a billion (1E9) digits.

Obviously straightforward multiplication isn't going to work because the largest number that can be represented by XPL0's double-precision reals is 1.79E308, which is a far cry from a billion digits. Here's how to find the answer using logarithms:

\N!.xpl 2-Mar-2010

\Use 32-bit XPL0 (xpx.bat) for speed and accuracy

include c:\cxpl\codes;

real N, A;

[N:= 0.0; A:= 0.0;

repeat N:= N + 1.0;

A:= A + Log(N);

until A >= 1E9-1.0;

RlOut(0, N);

];

If this program intrigues you, you'll probably be interested in Project Euler. It offers hundreds of

similar challenges. Although XPL0 has been used to solve at least 102 of

the problems on this site, it's not posted as one of the recognized

languages because so few people use it. Perhaps you can help change

that.

\Maze.xpl 24-Jul-2009

\Random Maze Generator

def Cols=10, Rows=6; \dimensions of the maze (cells)

int Cell(Cols+1, Rows+1, 3); \cells (plus right and bottom borders)

def LeftWall, Ceiling, Connected; \attributes of each cell (= 0, 1 and 2)

code Ran=1, CrLf=9, Text=12; \intrinsic routines

proc ConnectFrom(X, Y); \Connect cells starting from cell X,Y

int X, Y;

int Dir, Dir0;

[Cell(X, Y, Connected):= true; \mark current cell as connected

Dir:= Ran(4); \randomly choose a direction

Dir0:= Dir; \save this initial direction

repeat case Dir of \try to connect to cell at Dir

0: if X+1<Cols then if not Cell(X+1, Y, Connected) then \go right

[Cell(X+1, Y, LeftWall):= false; ConnectFrom(X+1, Y)];

1: if Y+1<Rows then if not Cell(X, Y+1, Connected) then \go down

[Cell(X, Y+1, Ceiling):= false; ConnectFrom(X, Y+1)];

2: if X-1>=0 then if not Cell(X-1, Y, Connected) then \go left

[Cell(X, Y, LeftWall):= false; ConnectFrom(X-1, Y)];

3: if Y-1>=0 then if not Cell(X, Y-1, Connected) then \go up

[Cell(X, Y, Ceiling):= false; ConnectFrom(X, Y-1)]

other []; \(never occurs)

Dir:= Dir+1 & $03; \next direction

until Dir = Dir0;

]; \ConnectFrom

int X, Y;

[for Y:= 0 to Rows do

for X:= 0 to Cols do

[Cell(X, Y, LeftWall):= true; \start with all walls and

Cell(X, Y, Ceiling):= true; \ ceilings in place,

Cell(X, Y, Connected):= false; \ and all cells disconnected

];

Cell(0, 0, LeftWall):= false; \make left and right doorways

Cell(Cols, Rows-1, LeftWall):= false;

ConnectFrom(Ran(Cols), Ran(Rows)); \randomly pick a starting cell

for Y:= 0 to Rows do \display the maze

[CrLf(0);

for X:= 0 to Cols do

Text(0, if X#Cols & Cell(X, Y, Ceiling) then "+--" else "+ ");

CrLf(0);

for X:= 0 to Cols do

Text(0, if Y#Rows & Cell(X, Y, LeftWall) then "| " else " ");

];

];

The maze consists of a rectangular array of cells, each with a wall on

its left side and a ceiling above. When the maze is generated, some of

these walls and ceilings are eliminated to form "Connected" pathways.

The 'case' command executes one of the four statements that follow depending on the value in Dir, which is either 0, 1, 2 or 3. Doubly nested 'for' loops are used in the main procedure to set up the array and then to display the maze. The values 'true' and 'false' are used to indicate the presence of a wall or ceiling and whether or not a cell is connected to other cells, thus forming pathways.

Note that the second 'def' (define) declaration does not specify any values. In this case the values assigned are 0, 1 and 2. The names are "enumerated" so each has a distinct value.

Because the ConnectFrom procedure calls itself (recurses), this program is doing more than meets the eye. If you redefine Cols and Rows to be much larger, you'll need to use 32-bit XPL0 to avoid a stack overflow.

+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+

| | |

+ +--+--+--+ + + + +--+ +

| | | | | | | |

+ + +--+ +--+ + + +--+--+

| | | | |

+ +--+--+--+--+ + +--+--+ +

| | | | | | | |

+ + + + + + + + +--+ +

| | | | | | | | |

+ + + + +--+--+--+ + + +

| | | |

+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+--+

Last update: 16-Nov-2015